- Home

- Robert J. Harris

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Page 3

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Read online

Page 3

His mother laughed but before she could speak there came a sharp rap at the door. Wiping her hands on her apron, Mrs Mary Doyle scurried to answer it.

On the threshold stood a small, portly man in a grey tweed suit and bowler hat. Behind him Artie recognised the policeman he and Ham had encountered in the fog last night.

“I am Lieutenant Sneddon of the Edinburgh Constabulary,” said the little man proudly, as if he were presenting himself as the Emperor of China.

McCorkle drew himself up to attention, waiting to be introduced, but Sneddon ignored him and continued in the same grandiose tone, “I am here to interview a resident of this domicile.”

Artie’s heart skipped a beat. Had McCorkle changed his mind about the two boys’ innocence? Had he tracked down this address and summoned his superior? He quickly stepped back into the shadows of the parlour, where he could observe the visitors without being seen.

“By name,” said Sneddon, “of Mr Benjamin Warren.”

“Ben?” said Mary Doyle, taken aback. “Why, whatever could you want with him?”

“That, madam, is a police matter,” Sneddon responded sharply.

The door to Warren’s room opened and the student peered out. “Me? Are you looking for me?”

“If you are Mr Benjamin Warren of the Edinburgh School of Medicine, then I most certainly am. Might we have a word in private?” Sneddon glanced meaningfully at Artie and his mother.

With obvious reluctance, Warren backed into his room and the two policemen followed, closing the door behind them. At the same moment Charles Doyle appeared, looking bleary eyed and confused.

“Visitors?” he asked his wife. “Is it someone from the gallery about my request for an exhibition?”

“I’m afraid not, dear.” Mary Doyle took him gently by the arm. “Callers for Dr Warren.”

“Mr Warren,” Artie corrected her. “He’s not a doctor yet.”

“Don’t quibble, Arthur,” Mary Doyle chided as she led her husband back to the bedroom.

Finding himself alone, Artie took the chance to press his ear to Warren’s door. The voices were muffled and he could only make out a few words and phrases. Warren said something about being exhausted from his studies and Sneddon mentioned that he had been reprimanded for missing a number of classes.

The detective’s voice abruptly grew sharper and more distinct as he inquired, “I would like to ask a few questions concerning your whereabouts last night.”

Artie pressed his ear even harder to the door, not wanting to miss any of Warren’s reply… until he was grabbed by the arm and jerked away.

“Arthur, this is not the behaviour of a gentleman,” his mother scolded. “Spying on people!”

She dragged him roughly into the kitchen.

“Surely you want to know what’s going on,” Artie protested.

Mary Doyle pushed him down in a chair and stood before him with her fists on her hips. “It’s no business of ours, I’m sure.”

“But the police,” Artie insisted. “Warren might be a thief, or a forger… or worse.”

“Don’t be absurd,” said his mother scornfully. “Why should a doctor engage in any such shenanigans?”

“He’s not a doctor,” Artie asserted again.

“He’s in training to be one, so he’s a doctor in potentia, which is practically the same thing.”

“If he’s so innocent,” said Artie, “why are the police looking for him?”

“The police often seek the assistance of medical men – to examine dead bodies for evidence and whatnot.”

When Artie tried to speak again she pressed a stern finger to his lips to quiet him.

“I’ll hear no more of this nonsense,” she stated firmly. “Ben has been a great help to us. Why, when Lottie came down with that fever, she might not have pulled through without his care. And your father’s seizure…” Her voice tailed off and Artie remembered Warren lifting the stricken Charles Doyle from the floor and carrying him to bed. He lowered his eyes, resentful of his mother’s gratitude towards the interloper. Surely it was he – Artie – who should step up and act as the man of the house when his father was ill.

Mrs Doyle turned and saw the pot of porridge boiling over. “Oh good heavens!” she exclaimed. She grabbed a long wooden spoon and began stirring with furious concentration.

Artie spotted the two policemen emerging from the lodger’s room. Warren paused in the doorway behind them, looking disturbed and pale.

“Now, mind and keep yourself available for future interviews,” Sneddon cautioned him.

“Yes, yes, of course.” Warren retreated into his room and closed the door.

Mrs Doyle was fully occupied with rescuing her endangered porridge and so did not notice Artie slipping out of the kitchen. He hurried to the front door and opened it a touch, so he could hear the two officers talking as they walked down the stairs.

“Medical men are a shifty bunch, McCorkle,” Sneddon was saying. “I’ll not trust any man that knows more about my own insides than I do.”

“I’m sure you’re right there, sir,” McCorkle answered woodenly, as though this was a response he was compelled to give at least twenty times a day.

“Aye, it’s a dark business with murky medical motives,” Sneddon went on. “But mark my words, I’ve more than a shadow of a hint of a suspicion that the Gravediggers’ Club is somewhere behind it all.”

As the two men passed out into the street beyond his hearing, Artie stood in the doorway, frozen with excitement over what he’d just heard.

“The Gravediggers’ Club,” he repeated to himself under his breath. “They’re behind it all.”

He went back to his room and opened his journal. Taking up his pen, he amended the heading of the case to: The Case of the Greyfriars Graverobbers The Mystery of the Gravediggers’ Club.

5. Interview with a Gravedigger

“A club?” said Ham. “Why would gravediggers have a club? It’s not like they’re the jolliest fellows.”

“Lots of people have clubs,” said Artie. “Why shouldn’t gravediggers have one?”

“I can’t think their meetings would be much fun,” said Ham. “Not unless there was plenty of lemonade and pudding.”

They were seated at a table in Ham’s front room later the same day. Ham lived with his mother, Mrs Lucinda Hamilton, who was giving a piano lesson to one of her pupils across the hallway. Ham’s father had died a few years ago and it was difficult for her to make ends meet. The piano lesson wasn’t going well. Artie stuck a finger in his right ear to block out the din of a ten-year-old girl murdering Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’. With the other hand he flicked through the pages of that day’s newspaper.

“I say, what are you doing with that paper?” said Ham. “You’re making a proper mess of it.”

“I’m looking for funerals,” Artie answered distractedly, running his finger down a column of newsprint.

“I don’t like funerals.” Ham made a face. “I was at my cousin Colby’s funeral last year. It rained, everybody was miserable, Uncle Ross and Aunt Bess got into a fight, and at the supper afterwards there was hardly anything to eat.”

“Ah, here’s the thing!” Artie exclaimed. He was so excited he even pulled his finger out of his ear.

“What are you so worked up about?”

“Listen to this.” Artie started to read aloud from the paper.

OBITUARY

Mr Hamish Gowrie will be buried at the Grange Cemetery on Saturday, January 20 at two o’clock in the afternoon. Friends and relatives of the deceased are cordially invited to attend.

“I’m sure that’s very interesting,” Ham yawned, “but what’s it got to do with us? We’re not his friends or his relatives.”

“Don’t you see?” said Artie. “For one, it’s the next graveyard on Warren’s list. And it means that somebody must be digging poor Mr Gowrie’s grave in the morning. This is our chance to interview a gravedigger.”

“I’m not

sure I want to interview a gravedigger. They’re probably not very sociable, what with hobnobbing with the dead and all.”

“We are going to investigate this mystery!” Artie declared. “If our lodger Mr Benjamin Warren is involved, it is vital that I expose him so that my family aren’t suspected of any wrongdoing – or put in danger. Or would you rather stay at home and eat cakes?”

Ham turned away guiltily. “Well, of course, when you put it like that, it’s a lot better to be out solving mysteries. I suppose.”

“Good,” said Artie. “Because with all those buns, you’re in danger of becoming stout.” He buried his nose in the paper, searching for any other items of information that might bear upon the case.

Ham lowered his gaze and mumbled, “My mother says stoutness is becoming in a man.”

***

Next morning, the boys set out together for the Grange Cemetery, which fortunately was in their own area of town. The trees and bushes were flecked with frost and the sky was dark with the threat of snowfall. When they reached the entrance to the graveyard Ham stopped and shook his head unhappily.

“Really, Artie, this obsession with graves is getting a bit unhealthy. If we must investigate your lodger, are there no other leads to follow? Does he have any less gruesome hobbies?”

“What kind of hobbies?” Artie fixed his friend with a hard stare.

“I don’t know. You’re the one who lives with him. Does he go fishing?”

“Fishing?” echoed Artie. Memories flashed through his mind of how he and his father used to fish for brown trout in the River Almond, back when Charles Doyle was healthy and full of life. It hurt to think those days might never return.

“I’ve seen no suggestion that Warren goes fishing, and I’ve never heard of a fishing-related scandal,” Artie snapped.

“Shame, I would much prefer a day’s fishing to a trip to a cemetery.” Ham had not noticed his friend’s irritation. “Just imagine the thrill of reeling in a really big fish and landing it.”

“And I suppose once we’d caught this enormous fish we’d cook him and eat him,” said Artie.

“Well, that goes without saying,” Ham enthused. “Pan-fried, I think, with butter and parsley.”

Artie couldn’t help grinning. “Ham, it’s no wonder you’re named after a kind of food.”

“Actually my name is Edward. It’s only you and the other chaps at school that call me Ham.”

“Well, we’re not abandoning our investigation in order to fill your dinner plate,” Artie insisted. “Now come on.”

He led the way into the cemetery. Under the sullen sky it looked an unhappy place, with a chill breeze tossing dead leaves among the gravestones. It was strange in this setting to hear somebody singing a Rabbie Burns song.

“Oh! what is death but parting breath?

On mony a bloody plain

I’ve dared his face, and in this place

I scorn him once again!”

“Where’s that coming from?” Ham wondered.

“This way.” Artie followed the sound of the song.

Weaving among the tombstones, they caught sight of a figure standing up to his waist in a grave, tossing up lumps of dirt with his shovel. The shape of the grave was marked out with a wooden frame and on the far side was a large box, towards which most of the earth was flying.

The gravedigger was a grizzled, brawny man with rolled-up sleeves and a kerchief tied around his brow. He swung his shovel in time with the rhythm of his song.

“Now farewell light – thou sunshine bright,

And all beneath the sky!

May coward shame disdain his name,

The wretch that dares not die!”

“That must be hot work, even in cold weather.” Artie hailed the man in a friendly voice.

The gravedigger stopped his singing and looked up. He planted his shovel in the earth and crossed his arms over the handle. “Aye, ye’ll have guessed that from my beet-red face.”

“Especially at this time of year,” said Artie, “when the ground is frozen solid.”

“It is that,” said the gravedigger. “Are you two lads here to lend John Dalhousie a hand?”

“What? In digging a grave?” Ham squeaked.

“There’s nothing to be afeart of,” John Dalhousie assured him with a mocking grin. “There’s nobody dead in here yet.”

“Well, I don’t know about digging,” said Artie. “We’re not really dressed for it. But I could offer you something to drink.”

“Drink is it?” said the digger, his eyes lighting up. “A nip of whisky maybe? A drop of gin?”

“More refreshing than that,” said Artie, pulling a bottle out of his pocket. “Ginger beer.” He held it out to Dalhousie who grasped it in his large, muck-encrusted hand.

“Ginger beer you say? Well, I reckon that’s better than no beer at all to a man with a thirst.” He tugged out the stopper and took a swallow that made him grimace in distaste. “It’s ower sweet for a grown man.”

Artie reached out to take the bottle back but the gravedigger ignored him and tilted it upward into his mouth. He gulped the lot down in five or six huge glugs then smacked his lips and wiped the back of his hand across his mouth.

“Well,” he declared, handing the bottle back, “it was better than vinegar or the slops out of the privy, so I thank you for it.”

He took a grip on the shovel and prepared to resume his task.

“I was wondering…” Artie interrupted.

The digger’s eyes swivelled up. “You was wondering what?”

“Well, if you and the other diggers – your brothers in the noble art of the spade – ever meet, you know, socially.”

Dalhousie leaned on his shovel again and fixed a curious eye on the boys. “How do you mean exactly?”

“Well, whether you get together to exchange stories of the many interesting sights you must have seen.”

“Interesting, eh?” Dalhousie paused for a moment then, darting his head forward said loudly, “Do you mean GHOSTS?”

Artie was so startled he had to stifle a yelp and Ham nearly fell over. As Dalhousie laughed, the boys pulled themselves together.

“I wasn’t thinking about ghosts so much,” said Artie.

“I say, you haven’t seen any ghosts, have you?” Ham asked. There was a tremor in his voice as he glanced round the cemetery.

“It may be that I have and it may be that I haven’t,” the gravedigger responded mysteriously, “but I’ll wager I could tell tales that would scare the breeks off you.”

“What I was actually thinking,” said Artie, “was that maybe you and your fellow diggers might get together to discuss the technical points of your craft. Say, the best kind of shovel or the difficulty of digging through clay.”

“I dare say them topics has come up a time or two,” Dalhousie conceded. “Grave topics, you might say.” He chortled at his own joke.

“Exactly!” Artie felt he was making progress at last. “Isn’t there some place where you meet to talk about such things?”

The digger rubbed his unshaven chin. “Well, sometimes, of an evening, Lucius Bream, myself and a few others do get together for a pot of light ale at the Rooster and Trumpet.”

“The Rooster and Trumpet?” Ham echoed quizzically.

“Aye, the public house in the Grassmarket,” said the gravedigger. “The beer’s not the best, but it’s cheap enough for my purse.”

“So I suppose it’s a sort of club,” Artie probed, “for gravediggers.”

“You could call it that if you was minded to,” said Dalhousie in an offhand manner. Then his brow darkened suspiciously. “Why so curious about us gravediggers?”

Artie flinched. He couldn’t let this man know that he suspected him and his friends of body-snatching.

“Oh, it’s my friend Mr Hamilton.” He grabbed Ham by the shoulder and pulled him forward. “He has a burning ambition to be a gravedigger.”

Ham was about to deny the wh

ole notion when he spotted how Artie was frowning at him and knew he had to play along.

“Oh, right, me, a gravedigger,” he stammered unhappily.

Dalhousie stared at him sceptically. “So what was it inspired you with this ambition?”

Ham stared at the man blankly.

“Well, go on, Ham, tell him,” Artie urged. “It was at school, wasn’t it?”

“Er… yes. It was when we were studying Shakespeare’s play Hamlet,” Ham improvised hastily. “You know, there’s that scene where the hero, Hamlet, has a conversation with a gravedigger.”

Dalhouise gave a dry chuckle. “Aye, whenever I dig up a skull I pick it up and have a wee chat, saying those lines from the play: Alas, poor Yorick…”

“Yes, digging graves has become Ham’s passion,” said Artie. “He’s even been practising in his own garden. Go on, Ham, show him.” He gave his friend a nudge in the ribs.

“Yes, I’m frightfully keen,” Ham agreed without much enthusiasm. He mimed grabbing hold of a shovel and digging in the ground.

The gravedigger eyed him critically. “Your technique is badly lacking. You need to get your back into it.”

Ham made his digging more vigorous, swinging his arms up and down until he was exhausted. Finally he laid down his imaginary shovel and stood panting.

Dalhousie shook his head. “You’re maybe better suited to some other line of work. A cobbler maybe, or a baker.”

GRRRRRROWF! WOOF! WOOF!

At that moment a wild barking sounded across the cemetery and a chill of fear ran down Artie’s spine.

“The hound!” Ham squeaked. He was so startled he lost his balance and Artie had to catch him before he fell into the open grave.

“That’s nothing to be frighted of,” laughed Dalhousie, pointing to a yelping corgi darting among the headstones, trailing its leash behind it.

An elderly lady was running unsteadily after it crying, “Come back, Hamish! Naughty boy! Naughty boy!”

As the woman and her errant dog disappeared behind a marble monument, Artie and Ham tried to shake off the embarrassment of being so easily scared.

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine Jason and the Gorgon's Blood

Jason and the Gorgon's Blood Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire

Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire Odysseus in the Serpent Maze

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze The Day the World Went Loki

The Day the World Went Loki The Thirty-One Kings

The Thirty-One Kings Thor Is Locked in My Garage!

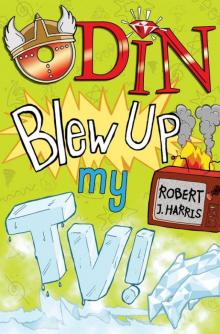

Thor Is Locked in My Garage! Odin Blew Up My TV!

Odin Blew Up My TV!