- Home

- Robert J. Harris

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Page 5

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Read online

Page 5

“The Lord himself healed the sick on the Sabbath,” said his father. There was more colour in Charles Doyle’s pale cheeks today, as if the short walk to church and back under a bright blue sky had done him some good.

“Quite correct,” his wife agreed. She stared disapprovingly at Artie, who was wolfing down his food as fast as he could without choking. “What are you in such a hurry for?”

“Ham and I have a project we’re working on today.” Artie scooped up the last of the beef onto his fork and delivered it to his mouth.

“A project?” said Charles Doyle. “Might that also be deemed working on a Sunday?”

“Perhaps you should leave your school work alone today and set your mind on higher things,” Mrs Doyle cautioned.

As he chewed, Artie tried to come up with a story that would satisfy both his parents. If they knew what he was really up to, they would probably keep him locked in his room until it was time to put him on the train back to Stonyhurst College.

“We’re writing a history of the church,” he said. “To go in the school library.”

“A history of the church?” his father repeated. “That sounds ambitious.”

“And unlikely.” His mother raised her eyebrows.

“Well, it’s a brief history, actually,” Artie corrected himself. “But I’ll be illustrating it with drawings of some famous saints.”

Charles Doyle was delighted. “Really? You must show them to me when they’re done.”

“Of course,” said Artie, rising from his chair. “I’d better get going. Ham will be wondering what’s become of me.”

“You will wait until everyone has finished,” his mother informed him in a steely tone.

Artie sank back into his seat, as though pressed down by a huge weight. He rubbed his hands impatiently on his rough, woollen trousers as he watched the rest of the family eat with annoying slowness. His two sisters, Lottie and Connie, were dawdling their way through the meal and it felt like they might never finish. At last, when all the plates were cleared and Mr Doyle had said the traditional grace after meals, Artie was allowed to leave.

***

Artie arrived at Ham’s house to find Mrs Hamilton forcing her son to practise scales on the piano. However, Ham’s gratitude for the rescue was short lived.

“Let me get this clear,” Ham said as they headed into town. “Your latest ridiculous idea is that your lodger stole the bodies to try to bring them back to life, then threw them in the quarry when he was finished.”

“That’s right,” said Artie. “All I need to do now is to consult an expert on the matter.”

“If you know a man who can raise the dead,” Ham declared, “I most certainly do not want to meet him!”

“I never said Dr Harthill could raise the dead. He’s an expert in medical science and electricity, so he will know if such a thing is possible. He will also know who could be performing such experiments, someone Warren might be in league with.”

“That doesn’t sound quite so bad,” said Ham. “But I’m warning you, Artie, if we go in there to find corpses staggering around with sparks popping out of their eyes, you can fight them off yourself. I’ll be gone before you can say Franklin Stone.”

“Frankenstein,” Artie corrected him.

“Well, whatever, I’ll be gone in a flash. How did you meet this doctor chap anyway?”

“Last summer he advertised an electrical treatment he’d developed in The Scotsman newspaper. The advert said it could cure all manner of ailments so I went to visit him and we hit it off.”

“What did you want to see a doctor for?” asked Ham. “You’re not sick, are you?”

“Never mind about that,” said Artie abruptly. “The point is, he’s a very clever man who knows a lot about science, especially the power of electricity.”

***

They arrived in Rutland Square, which, in keeping with the design of the New Town, was broad and spacious. At its centre was a private park with carefully tended lawns and tall, elegant trees, surrounded by orderly rows of terraced townhouses with large bright windows.

The boys climbed the four steps to Dr Harthill’s shiny black door, which was flanked by a pair of Grecian-style pillars. The nameplate read: Dr William Harthill, Medical Galvanist.

Fixed to the door was a sign: Successful treatment in the cases of Indigestion, Headache, Nervous Palpitation, Depression of Spirits, Costiveness, Rheumatic and Neuralgic Pains, Paralysis and Nervousness from whatever cause arising. Free consultation Daily from 11 am to 4 pm, and 7 pm to 9 pm. The Galvanic Treatment is guaranteed to give neither Shock nor Pain.

Artie rang the doorbell and waited for a reply.

After half a minute Ham let out a sigh of relief. “He must be out on his rounds. That’s too bad. Let’s be off home then.”

Before he could take a step, Artie seized him by the arm. “He’s probably just too busy to answer the door.” He tentatively tried the handle of the door and found that it was unlocked. “Come on.” He beckoned his friend inside.

“Artie, are you sure we should just walk in like this?” Ham worried.

“It’s quite all right,” Artie assured him. “I told you, the doctor and I are good friends.”

The moment Artie stepped over the threshold into the hall there was a crash of breaking glass, and a flash of lightning across the high ceiling. He reeled back in shock as a shower of sparks came swirling through the air towards him.

9. A Word with the Electrical Wizard

Artie yelped and threw his arms up protectively in front of his face as sparks flickered all about him. When he lowered them, the electrical disturbance had ceased, leaving only a whiff of ozone in the air. Ham stepped cautiously into the hallway beside him, wide-eyed with alarm.

“Artie, what was that?” he asked.

Artie quickly pulled himself together and spoke confidently. “It’s quite all right, Ham. It will just be one of the doctor’s experiments. Come on in.” They walked down the hallway, taking in the coils of blackened wire that dangled from the ceiling and shattered fragments of glass tubing that littered the carpet.

“Artie, are you sure you should be keeping company with someone as dangerous as this?” Ham asked, crunching a piece of glass beneath the sole of his boot.

“Oh, Dr Harthill’s not dangerous,” said Artie. “He’s a real registered doctor. He just has lots of interesting and innovative ideas about medicine and science.”

“Like this, for instance?” Ham paused to stare at a large diagram on the wall. “What on earth is this supposed to be?”

It was a drawing of a bald human head, the scalp criss-crossed with lines dividing it into labelled sections.

“Oh, that illustrates the principles of phrenology, the science of examining the skull,” Artie explained. “From the shape of a man’s head you can tell what sort of character he has, whether he’s an intellectual, an artist or even a criminal.”

“Are you saying a chap could be arrested just for the shape of his head?”

“I suppose that would be carrying it a bit too far. You’d still have to prove that he’d committed a crime.”

“But if he had a criminal head, shouldn’t you arrest him right away to keep him from committing a crime?”

“I think judges and lawyers would have a hard time wrestling with that,” said Artie. “But I would like the opportunity to examine Benjamin Warren’s head. I’m sure I would find some criminal bumps on his skull.”

Artie led Ham down the long hallway, past framed scientific diagrams and photographs of grey-bearded, balding men posing at various medical conferences.

“And what was that sign on the door about Calvinism?” asked Ham.

“Not Calvinism, you dunce – galvanism. It’s named after the Italian scientist Galvani who showed that you can make a dead frog’s leg twitch by passing electricity through it.”

Ham wrinkled his nose in distaste. “For goodness’ sake, Artie, who would want to electrify a dead fro

g?”

“The theory is,” Artie told him patiently, “that if electricity can enliven the nerves of a dead frog, perhaps it can restore health and vigour to sick people.”

BZZZ-ZZZZZZ-CRRRREEAACKKK-FFFFF

“Listen, what’s that noise?” Ham exclaimed.

A sporadic buzzing and crackling was coming from the door at the far end of the hallway.

“That’s Doctor Harthill’s laboratory,” said Artie as they approached it. He knocked, but once again there was no reply. He opened the door – this time very cautiously.

A powerful tang of ozone suddenly stung their nostrils and flashing zigzags of light forced them to shield their eyes.

Between the flashes of light, they glanced around to see shelves and tables supporting a dazzling array of scientific equipment.

There were large bottles of acid labelled with chemical formulae like H2SO4. Round plates of copper, iron and zinc had been stacked in columns and submerged in tanks of coloured liquid. Metal spheres crackled with sparks and all across the room trailed thick cables that buzzed continuously with electrical current.

In the middle of all this, in a large, wooden chair, sat Dr William Harthill, a wiry figure with a shock of silvered hair. He was in his shirtsleeves and fastened around his middle was a leather belt covered in a weave of metallic fibres. Coils of wire connected the belt to a series of batteries on a nearby table.

The doctor was so absorbed in feeling his own pulse and checking a row of dials that at first he didn’t notice the visitors. The two boys stood in stunned silence amidst of the electrical chaos until he finally realised they were there.

“Ah, Mr Doyle!” Harthill exclaimed, his lean features lighting up in a welcoming smile. “How fortuitous that you should happen by!” He flicked a switch that protruded from the arm of his chair then unfastened the belt from around his waist. He stood up and stretched, then puffed out his chest like a man taking in a breath of fresh sea air.

“Dr Harthill,” said Artie, “there’s been some sort of explosion in the hallway.”

“What, again?” The doctor tutted to himself. “I have been trying to light the hall using electricity but the filaments keep overheating and blowing out the tubes. Most unsatisfactory.”

“I hope we’re not interrupting,” said Artie. “My friend Edward Hamilton and I wanted to ask you a few questions about galvanism.”

“If it’s a bad time we can just leave.” Ham cast an eager glance at the door.

“Not at all, not at all.” The doctor took an old tweed jacket from a nearby peg and slipped it on. “The two of you are the first to witness the workings of the new Harthill Galvanic Belt,” he announced proudly. “The effects are truly remarkable.”

“What does it do?” Ham inquired dubiously. “Give you the strength of ten men? Help you to live for a hundred years?”

“Nothing so frivolous, my young friend,” Dr Harthill laughed. “No, no, no, this is a true breakthrough which will bring the most wondrous benefit to the human race. It is – at last – a complete and definitive cure for indigestion.” He clapped his hands together and beamed with delight at his triumph.

“Am I understanding you right, Dr Harthill?” Artie gestured at the array of scientific equipment. “All of this is to cure indigestion?”

“Precisely!” the doctor enthused. He cast an eye over Ham and said, “You, my fine fellow, are surely familiar with the pain of indigestion that frequently follows a heavy meal.”

“I wouldn’t say that,” Ham mumbled.

“In our modern times,” Dr Harthill resumed, “when people consume unhealthy amounts of pies, dumplings and puddings, indigestion has become a blight upon society. But now that the power of electricity can provide relief, diners need not worry about the consequences of over-eating. Thanks to the Harthill Galvanic Belt, intestinal discomfort will be a thing of the past.”

“I’m sure it’s very useful,” said Artie, “but you’d need a whole room for all the equipment.”

Doctor Harthill scurried briskly about, flicking switches and pulling levers until the buzz and crackle of his electrical batteries subsided to a low hum.

“Oh, this is merely an experimental model, my boy. The final product will be quite portable. And,” he added with a bright smile, “the sensation is so mild and soothing, even an infant could bear it.”

“Artie, I don’t know about you,” said Ham in a confidential tone, “but I’d rather put up with a tummy ache than be wired up to all this gubbins.”

Dr Harthill made a final adjustment to his equipment then turned back to face the boys. “So, Mr Doyle, has your father shown any signs of improvement since you brought him to me for treatment?”

Artie’s heart sank at the thought of his father’s declining condition. “I can’t say that he has, sir, much as I wish he would.”

“Hmmm… unfortunate. Perhaps if I adjust the voltage.”

“The world presses down on him, sir, and he hasn’t the strength to bear the weight.”

“Ah, well,” said the doctor, “even the marvels of electrical science have not yet developed to the point of curing the spirit. But one day…” He raised a finger to demonstrate his confidence in the future.

“Actually, Dr Harthill,” said Artie, “we’re here to ask your advice about a recent spate of crimes that have the police baffled. We’ve been making some inquiries of our own.”

“Good, good,” Harthill enthused. “I believe an inquiring mind is the most important thing in the world.” He perched himself on the edge of the chair. “So tell me all about it.”

Artie gave him a brief account of the recent grave robberies, explaining how the stolen corpses had reappeared without any sign that they had been used for anatomical research.

“It is most curious,” Harthill agreed. “And yet I don’t see what insight I can offer.”

“Well,” Artie continued hesitantly, “I read a book in which it was suggested that electricity could be used to bring dead bodies back to life. Could our suspect have been attempting to do such a thing?”

Harthill let out a short, sharp laugh then stifled it by slapping a hand over his mouth.

“Forgive me,” he said. “I don’t mean to mock, but really…”

“But the frog, the twitching leg…”

“Mere reflex,” said the doctor dismissively. “No, no. No amount of galvanic force can reanimate a body once the soul has flown. Only God could do that.”

Artie’s face turned red with embarrassment and frustration. “But you’ve proved how many ailments can be cured by electricity.”

The doctor raised a hand to cut him off. “My boy, if you take a spoonful of tonic, it will give you renewed vigour. We can agree on that. But that doesn’t mean that if you pour a bucket of tonic over a dead body it will miraculously spring to life and start dancing around the room, does it?”

“I suppose not,” Artie conceded. “Then I have no idea why all those bodies were dug up. There must be a reason – and I can’t shake off the feeling that Warren was involved.”

“Sometimes, Artie, a mystery is just a mystery.” Ham tried to console his friend. “There’s no point beating your brains over it.”

“I’m not interested in just saying it’s a mystery and using that as an excuse to give up,” said Artie stubbornly. He looked to Dr Harthill, who appeared to be lost in thought.

The doctor suddenly emerged from his reverie and jumped to his feet. “Your perseverance does you credit, my young friend.”

“Do you have an idea then?” Artie inquired hopefully.

“Perhaps,” said the doctor with an impish gleam in his eye, “you should be thinking about magic.”

10. The Ghost Walks Again

“Magic?” Artie repeated incredulously. “Surely you don’t believe in magic, doctor?”

“What? No, no,” said Harthill, “not in spells and black cats and all that superstitious mumbo jumbo. No, I mean stage magic – which is of course trickery, but requi

res an impressive degree of skill and preparation.”

Artie scratched his head in confusion. “I’m afraid I still don’t follow you.”

“I was once approached by the magician John Henry Anderson,” said the doctor, “professionally known as the Wizard of the North.”

“He’s amazing!” Ham enthused. “We went to see him at the Palace Theatre and he made a lady float in the air and made a pony disappear and—”

“Yes, Ham,” Artie cut him off. “We’ve all heard of him, but what did he want with you, Dr Harthill?”

“He wished to incorporate some of my electrical apparatus into his stage performance,” the doctor replied, “to create spectacular effects. I told him I could not allow my research to be trivialised as mere entertainment. However, in the course of our discussions I learned one or two tricks of his craft. One of which is termed misdirection.”

Ham wrinkled his nose in puzzlement. “Miswhatsit?”

“Misdirection: the art of distracting the audience with one hand,” Doctor Harthill raised his right hand high above his head and wiggled his fingers, “whilst carrying out some unseen piece of trickery with the other.” He brought out his left hand from behind his back, holding a pencil he had plucked from Ham’s pocket.

“But what has that got to do with the grave robberies, sir?”

“Consider this possibility, my friend,” said the doctor. “Could it be that the discarded bodies are a distraction, causing the police and yourselves to investigate body-snatching for medical research? During which time you are not asking yourselves: What are these mysterious characters really digging up? Could there be something else hidden in those graves?”

***

This was the question Artie took away with him when they left the doctor’s office. As he and Ham walked along Rutland Street, he kept his hands thrust deep into his pockets and stared intently at the pavement, as though trying to reach an answer that lay hidden in the earth.

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine Jason and the Gorgon's Blood

Jason and the Gorgon's Blood Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire

Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire Odysseus in the Serpent Maze

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze The Day the World Went Loki

The Day the World Went Loki The Thirty-One Kings

The Thirty-One Kings Thor Is Locked in My Garage!

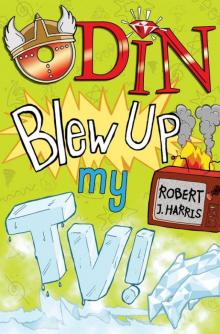

Thor Is Locked in My Garage! Odin Blew Up My TV!

Odin Blew Up My TV!