- Home

- Robert J. Harris

The Thirty-One Kings Page 5

The Thirty-One Kings Read online

Page 5

Jaikie took the wheel and drove off northwards with his eyes as much on the rear-view mirror as the road ahead. The surrounding city was still largely asleep, its long streets deserted apart from a few early-rising tradesmen and newsagents.

‘I’ve played some parts in the past,’ I said, ‘but I believe this is the first time I’ve passed myself off as a plumber. I just hope nobody expects me to mend a broken pipe, because they’ll be in for a flood if they do.’

‘It’s only for a short while until we reach our rendezvous point,’ Jaikie informed me. His eyes flicked towards the mirror.

‘Do you think anyone is following us?’ I asked.

‘If they are, they must be literally invisible. Still, it never hurts to take precautions.’

I had the tool bag in my lap and when I opened it I saw nestled among the rods and spanners a shoulder holster housing a Webley .38 revolver. When I lifted the weapon out, Jaikie said, ‘You can put that on when we stop. There’s a box of cartridges in there too.’

We drove past Regent’s Park and on to the outskirts of Highgate where we pulled inside a dingy-looking garage. The doors were shut behind us by two men who collected our discarded overalls. Another man dressed in a plain grey suit and cap beckoned us towards a waiting Bentley. Though he was in civvies, he gave us a stiff military salute as we got into the back seats. Here each of us found a small knapsack containing extra clothing and some basic toiletries.

Once our driver was behind the wheel, the other two men rolled up a steel shutter at the far side of the garage and we moved off through this rear exit.

‘This is quite the shell game,’ I remarked.

‘As a youngster in Glasgow,’ said Jaikie, ‘and an undersized one at that, I became pretty sharp at dodging pursuit by a gang or, on some occasions, the police.’

‘I’ve had to dodge both in my time as well, so I appreciate your expertise.’

Within the hour we had left London behind and were wending our way through the green level fields and tame woodlands of Middlesex. The light broadened steadily as our silent driver steered an unerring course along back roads and country tracks.

Jaikie pulled out a crumpled pack of Virginia cigarettes and offered me one. When I waved it away he popped it into his mouth and lit it, his brow crinkling in thought as he did so.

I slipped The Pilgrim’s Progress out of my pocket and opened it to the first page of the narrative. Here I read the words:

Moreover, I am for certain informed that this our city will be burned by fire from heaven; in which fearful overthrow both myself, with thee my wife, and you my sweet babes, shall miserably come to ruin, except (the which yet I see not) some way of escape may be found whereby we may yet be delivered.

These hard words might well be addressed to our own times. Yet I knew that Christian and his family did escape destruction, so there was hope for us as well.

When Jaikie’s eye lighted on the book I explained that it had belonged to Peter Pienaar, my mentor during my days in South Africa, who had joined me on some of my European escapades. He was a flier in the war but was shot down over Germany and held prisoner for several months. He passed much of that time reading the Bible and this book, sending me regular letters filled with his reflections on both.

He was eventually released as it was thought his injuries made it impossible for him to serve any further, but he proved everyone wrong, perishing in one final, vital mission.

‘Mary has been keeping it close by for me in case I should suddenly be called off on a caper like this,’ I said. ‘Just leafing through the pages makes me feel that my old friend and my wife are both here with me.’ I gave an embarrassed laugh. ‘You must think I’m an old sentimentalist.’

‘Not at all, sir. As it happens, I have a token from my lady too.’

From his pocket he produced a light brown feather flecked with black.

‘That belongs to a kestrel, doesn’t it?’ I guessed.

‘As a matter of fact it belongs to an even finer bird,’ said Jaikie proudly. ‘To Miss Alison Westwater who entrusted it to me for luck and as a token of her affection. She says that as I long as I hold on to this, I’ll always find my way back to her.’

‘She sounds like a remarkable young woman. Why haven’t you married her?’

Jaikie shifted uncomfortably. ‘I can’t do that yet, not until I’ve performed a great deed.’

‘And what might that be? Slay a dragon? Pull a magic sword out of a stone?’

Abashed by my gentle mockery, he said, ‘I don’t know, but I’ve been in training for years so that when the time comes I’ll not be found wanting.’

In my own youth I too fancied I had all the time in the world and thought adventuring and soldiering were the best things life had to offer. Now I knew better.

‘Take an old man’s advice,’ I said, ‘and don’t wait around for destiny to take a hand. As soon as we get back from this venture you get that girl to a church.’

Jaikie finished his cigarette and sat in silence until we entered Suffolk. A plane was waiting to take us to France and I assumed we were headed for an RAF base. Our actual destination came as a surprise.

‘Why, this is a race track,’ I declared.

‘Newmarket race track to be exact,’ said Jaikie, taking some mild enjoyment from my surprise. ‘The RAF are using one of the grass strips here as a runway. The great advantage, of course, is that this is an airfield the Germans won’t find on any of their maps. Ideal for a clandestine operation like this.’

Skirting the main gate, the driver took us round to a secondary entrance adjoining the main grandstand. At the northeast end of the enclosure we pulled up by a clubhouse where two men in suits and hats were waiting. As soon as we exited the vehicle they took our places and the car pulled off, heading back towards the main road.

Jaikie checked his watch again in obvious expectation.

‘Don’t tell me we have to ride horses next,’ I joked.

‘It’s not come to that,’ said a voice from the open door of the clubhouse.

A moment later a familiar figure stepped into view.

7

THE FLIGHT OF THE BLESSED ANTONIA

‘Archie Roylance!’ I exclaimed at the sight of my old friend.

In spite of the injury to his leg, which had plagued him for years, Archie approached us with a jaunty spring in his step. He was dressed in a flying suit with an RAF crest.

‘Dick,’ he greeted me cheerily, ‘I knew it was only a matter of time before you’d be off on some wild caper. It’s a pretty kettle of fish this time around, eh?’

As a young man Sir Archibald Roylance had been one of my subalterns in the old Lennox Highlanders until he left to join the Flying Corps. After the war he took up politics and diplomacy until he sickened of both and retired to his Scottish estate.

We exchanged hearty handshakes.

‘Archie, I thought they had you busy training new pilots.’

‘That’s right,’ Archie affirmed airily, ‘but they can’t keep me from sneaking back into action whenever the mood takes me. And I certainly wasn’t going to let some sprog who’s still wet behind the ears fly General Sir Richard Hannay into the middle of this set-to.’

He shifted his attention to my companion and his face lit up.

‘And bless me if it isn’t John Galt. How have you been, Jaikie? I haven’t seen you since that time you turned my pleasant Austrian jaunt into a king-sized pickle.’

Jaikie raised a cautioning hand, as if to keep Archie from saying anything further about that particular incident. ‘You know how it is, Sir Archie. I’ve been doing a bit of this, a bit of that.’

With an effort Archie stifled his Austrian reminiscences and regarded us with a broad grin, as though we were a pair of comic entertainers. ‘I swear I never met two chaps with such a talent for getting in and out of the hairiest scrapes. Dick, I first met Jaikie here when he was only a sprat.’

‘I remember it well,’ said Jaiki

e.

‘Back in those days you were one of that gang of ragamuffins old McCunn took under his wing. What did you call yourselves again? The Glasgow Divers, wasn’t it?’

‘Die-Hards,’ Jaikie corrected him. ‘The Gorbals Die-Hards. And we weren’t a gang. We couldn’t afford the cost of a uniform to join the Boy Scouts, so the six of us formed our own troop.’

Archie nodded sagely. ‘Yes, I remember now. Had your own flag and everything. So what became of the rest of the Divers?’

Jaikie didn’t bother to correct him again. ‘Oh, some of them are still around,’ he replied enigmatically.

‘Well, chaps, any further reminiscing will have to wait,’ said Archie, leading us towards a camouflaged hangar. ‘I don’t know exactly what you’re up to, but I do know I’ve to fetch you over to France before the day’s much older.’

‘You’ve received the flight plan, Sir Archie?’ Jaikie enquired.

‘Absolutely, Jaikie, maps and all. Though why you should want to be dropped off near some obscure French château is a bit of a poser.’

When we entered the hangar I saw a plane scarcely larger than a fighter with its wings set unusually high. Two mechanics in oil-stained coveralls were just finishing their pre-flight ground checks. They stepped away as we approached and one of them wiped his face with a rag.

‘We’ve done all we can, sir,’ he told Archie. ‘I reckon she’s as close to airworthy now as she’ll ever be.’

‘I’m sure she’ll do, Harry,’ said Archie. ‘I’m quite sure of that.’

The grey fuselage was marked with the familiar roundel of the RAF while the tail fin bore the tricolour of our French allies. More striking were the words painted in bright red beneath the pilot’s cockpit: The Blessed Antonia.

‘She’s a Westland Lysander,’ Archie told us proudly, ‘a grand old bus, and, as you can see, I’ve named her after my dear old Aunt Antonia.’

‘Would it be impolite to ask why?’ Jaikie hazarded. ‘Not at all,’ Archie responded jovially. ‘You see, when I was a boy, my sisters and I often spent the summer months with my Aunt Antonia, who was actually a cousin of my father once removed. Or maybe it was twice. Anyway, through all the months we spent with her during those childhood years, she never once let us down.’

Archie gave the plane an affectionate pat as he continued his story, almost as if his aunt were actually embodied in the aircraft.

‘If she had promised us a day at the beach, then off to the beach we would go, no matter if there was a gale blowing and rain lashing down. If she had promised us crumpets for tea, then crumpets there would be, even if she had to use the sharp end of her most dangerous umbrella to compel the baker to whip up a fresh batch. That’s why I’ve always referred to her as the Blessed Antonia.’

For a moment Archie’s eyes became misty, as though he were seeing again these scenes from his childhood. Then, recollecting himself, he ran his finger along the painted letters. ‘I decided that if I gave the same name to this venerable crate then she also would never let me down. And believe me, she’s already got me out of one or two tight spots.’

‘That much is obvious,’ I observed, noting that there were at least a dozen bullet holes marking the body of the plane.

‘Yes, she took a few hits during the Dunkirk operation,’ Archie acknowledged ruefully, ‘but she brought me back safe and sound every time.’

‘It looks pretty cramped in there,’ said Jaikie, peering into the passenger cockpit.

‘She was originally designed to carry only a single passenger,’ said Archie, ‘but she’s been modified to squeeze in two, provided neither one is on the stout side. Plus she only needs a short runway for take-off and landing. If need be, I swear I could bring her down on a tennis court.’

Archie climbed into the pilot’s seat and strapped on his helmet. I clambered into the passenger cockpit with Jaikie cramming in behind me. It occurred to me that, as well as his other qualifications, his ability to fit himself into such a narrow space might be another reason Blenkiron had selected him for this particular assignment. I had to loosen my shoulder holster and slide it around to keep the pistol from digging into my ribs and I could feel Jaikie squirming about behind me in quest of the least uncomfortable position.

Once our helmets were on and the cockpit closed, the ground crew cleared the chocks from under the wheels. The engine coughed into life and we rolled slowly out of the hangar. The two mechanics waved their farewells and one of them shook his head as though amazed we had made it even this far. Turning left, we taxied onto a flat stretch of green running parallel to the race track and began our take-off run. The roar of the engine and the whirr of the propeller rose to a high pitch as we gathered speed. With thirty feet of grass to spare, Archie deftly adjusted the stick and we lifted off the ground as gently as a feather swept up in a breeze.

It was so long since I had been up in a plane that I had almost forgotten the sheer exhilaration of flight. To see the earth dropping away below and the clouds rushing down on us from the azure sky made me feel as if all the heavy cares of the world were as insubstantial as a morning mist. We banked southwards, passing over a chequerboard of fields, with the sea a distant gleam to our left.

Archie had grown up around horses and his expertise as a rider had translated seamlessly into the skills of a pilot. However, like many an experienced horseman, he had a preference for the spirited sort of mount that offered a more challenging ride, and this had carried over into a particular liking for a more cantankerous aircraft. I heard the engine give an occasional splutter and I was sure that not every bump and jolt was due to the air currents.

Archie seemed to delight in these slight difficulties, handling the plane with the sure, light touch of a horseman coaxing his mount over a series of high fences. From the few unhappy grunts he was unable to suppress I guessed that Jaikie had never flown with Archie before and did not have the same confidence in his piloting skills that I had acquired in the last war.

As we passed over the Thames Archie swooped down to give us a view of the various vessels, both military and civilian, that were busily plying the waters. Off to our right a sooty smudge hung over the distant smokestacks of London and an RAF transport plane passed over us on its way to the city.

‘One of the new Bristol Bombays,’ Archie informed us over the radio. ‘Not a patch on the old Handley Page planes if you ask me.’

We flew over the once peaceful fields of Kent, now dotted with an array of early warning stations. Where once beacons would have been lit on the hilltops, now telephones and radios stood manned and ready to warn of an enemy attack.

As we skirted the coast I looked down on the choppy waters of the Channel. A Royal Navy cruiser and a smaller vessel, perhaps a fishing boat, were paralleling each other on a westward course. Most of our troops had been successfully pulled off the beaches, but I knew that some of our men were still making their way to the coast in dribs and drabs and the navy was on the lookout for any of them attempting to cross by rowboat or dinghy.

A sudden gust of wind struck us broadside, causing the Blessed Antonia to crow-hop sideways like a skittish horse. Jaikie let out an involuntary yelp.

‘Don’t worry, Jaikie,’ I assured him. ‘Sir Archie has got me through much worse than this.’

‘I don’t think I have much of a stomach for flying,’ Jaikie confessed. ‘To tell you the truth, I’d feel more at home on one of those boats down there.’

‘Not a bit of it, Jaikie,’ Archie called back cheerfully. ‘Safe as houses up here. Let me give you a few lessons and you’ll be as merry in a plane as you would be on the back of your favourite mare.’

‘Actually, sir, I’m not much of a horseman either.’

‘On your favourite bicycle then,’ Archie amended. ‘You take my word for it.’

Below us the lush green of Romney Marsh gave way to the bleached shingle of Dungeness. Here we parted company with England and struck out over open water with our own shadow chasing u

s across the waves.

As we closed on the French coast my earlier mood of pleasurable excitement was soon replaced by that quickening of the pulse and the prickle in my scalp that I always felt in the moments before a battle. This was hostile territory ahead, overrun by an enemy now more ruthless and coldly determined than ever before.

Rugged white cliffs reared before us, split by a broad river flowing out into the sea. At the base of the cliffs a seaside town straddled the estuary, its shops and houses as brightly painted as toys. An assortment of small boats bobbed at anchor inside a stone breakwater. Everything appeared peaceful but I felt as though a palpable chill had crept into the air.

Archie’s thoughts must have been running parallel with mine. ‘Our planes have all been pulled out of France,’ he said, ‘in spite of the promises Churchill gave to support them. Still, what choice did we have, eh? If France goes down, we’ll need every crate we can scrape up for the next battle.’

‘You mean the invasion?’ I said. ‘Surely we can hold the Channel against them.’

‘Not if they’re free to bomb the blazes out of our defences,’ said Archie. ‘No, the thing will be decided in the sky, you mark my words.’

I couldn’t tell whether this was an accurate assessment of the situation or merely sprang from Archie’s personal enthusiasm for air power.

‘Of course some of our chaps are still flying reccies over here,’ Archie resumed, ‘and even lending a hand where they can, whatever their orders. It’s hard to tell if the French are glad to see them or are resentful of our supposed betrayal - you know, perfidious Albion and all that rot.’

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine Jason and the Gorgon's Blood

Jason and the Gorgon's Blood Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire

Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire Odysseus in the Serpent Maze

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze The Day the World Went Loki

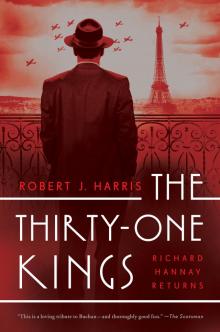

The Day the World Went Loki The Thirty-One Kings

The Thirty-One Kings Thor Is Locked in My Garage!

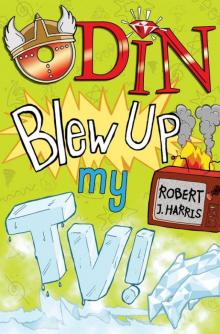

Thor Is Locked in My Garage! Odin Blew Up My TV!

Odin Blew Up My TV!