- Home

- Robert J. Harris

The Thirty-One Kings Page 8

The Thirty-One Kings Read online

Page 8

‘I think Mr John S. Blenkiron had as much of a hand in it as the Almighty,’ said Jaikie.

‘Blenkiron?’ Dougal made a face. ‘That’s a right queer name.’

‘He’s an American,’ said Jaikie, ‘but he’s always been in thick with our own military. He’s the one who put this team together.’

‘But how did he get wind of the Die-Hards?’ Dougal wondered.

‘Well, he’s been travelling the length of Britain establishing useful contacts,’ Jaikie explained, ‘and while he was in Scotland he made the acquaintance of Mr Dickson McCunn.’

‘I knew it!’ Dougal declared, smacking a fist into his palm. ‘I knew McCunn would be at the back of it somewhere. The man’s that deep, he’s capable of anything.’

‘Aye, I doubt we’ll ever get to the bottom of him,’ said Peter, speaking with the authority of a medical man.

‘Not without the help of a diving bell,’ joked Jaikie.

‘So what else has Mr McCunn been up to?’ Thomas asked.

‘He’s in command of his local Home Guard,’ Jaikie answered with a grin. ‘He’s as happy as can be drilling his motley crew of grocers and bank clerks. He marches them up and down the hill, just like the Grand Old Duke, then flings them all into a ditch to practise concealment.’

‘I dare say he’s applying his sound business principles to the matter of home defence,’ said Peter. ‘If any Germans ever make it as far as the Canonry, they’ll have the devil of a fight on their hands.’

‘Aye, old McCunn was never one to go down easy,’ Dougal agreed.

From what Archie and Jaikie had told me earlier, I gathered that the almost legendary Dickson McCunn was a retired Glasgow grocer who had taken the Die-Hards under his wing while they were still children. Acting as their protector and mentor, he had raised them out of poverty and paid for their education, so opening up the path that had led them to their present careers. To this day they held him in an esteem bordering on awe.

Two of the original Die-Hards were not present here, by name of Bob and Napoleon. One had long ago emigrated to Canada, the other to Australia, but Jaikie told his friends he had received word that both of their old comrades had found ways to serve the mother country in their adopted lands.

After relating this news, Jaikie directed them towards me. They stood to attention but I waved them back to their seats.

‘Relax, gentlemen. It’s years since I was last in uniform, so you don’t have to treat me like a general.’

‘If you don’t mind my asking, sir,’ Peter ventured, ‘what is a general doing in an operation like this?’

‘It’s not so much because of my battlefield experience,’ I replied, ‘though I’ve more than enough of that. It’s rather because I have a knack of stumbling into the right place at just the right time, partly by instinct and partly by sheer luck. This mission will need plenty of both.’

‘Well, sir, I suppose this is your army,’ said Jaikie. ‘Dougal here, Lieutenant Crombie, has always been our chief, and we follow him like he was Robert the Bruce.’

‘I thought I’d heard of you as somebody high up in the world of journalism, Lieutenant Crombie,’ I said.

‘Just plain Dougal will do fine,’ he said. ‘It’s true that my boss, Mr Craw of the Craw Press has done all he can to make me indispensable to his business, leaving him the leisure to enjoy the finer things in life. Just to keep him honest, though, I’ve made a habit of sending myself away on lengthy overseas assignments, forcing him to keep one foot in the business. When this trouble started brewing I appointed myself Chief Military Correspondent.’

He made a self-mocking show of the airs that should be expected of one with so grand a title.

‘I told Craw I wouldn’t sit behind a desk passing out propaganda. No, I was going to be out there on the front line with the troops. Well, Craw made a few phone calls and next thing I knew I was being put through officer training. He calculated it was a lot safer to make me an officer than to leave me in the ranks where I was liable to stir up a mutiny.’

‘Aye, we do sometimes have to hold Dougal back from sticking his head into the lion’s mouth,’ joked Peter.

‘I’m wise enough to follow our trusty scout though,’ said Dougal, placing a hand on Jaikie’s shoulder. ‘Jaikie could find his way blindfolded through a coal mine at midnight.’

‘Peter here, as you can see, is our medic,’ said Jaikie. ‘I expect Mr Blenkiron picked him out in case Mr Roland needs medical attention.’

‘If he’s been subjected to interrogation, that’s more than likely,’ I said.

‘Though I’m a healer now,’ Peterson asserted bullishly, ‘I’m still a Die-Hard and you’ll not see me shy away from a fight.’

I had no doubt of his fighting spirit, but now I turned to the fourth of the Die-Hards. ‘I see we have a chaplain as well. For our spiritual needs?’

‘The Reverend Thomas Yowney isn’t just here because he can recite half the King James Bible from memory,’ said Jaikie.

‘No,’ said Dougal, ‘the fact is, he’s the best man you’ll find for sheer brains north or south of the border. There’s no spot so tight that he can’t think his way out of it.’

Thomas’s three friends grinned at each other and chorused, ‘Ye’ll no’ fickle Thomas Yowney!’ They finished with a whoop of good-natured laughter that left their companion looking abashed.

‘They’re exaggerating, of course,’ he said diffidently. ‘But they mean well.’

In the last war I had commanded thousands of good men and had always taken pride in their courage and loyalty. I could tell even now that this little band from the slums of Glasgow would be among the finest I had ever served with.

I explained to them the outlines of what we were about to undertake and found them eager to tackle the mission. We were discussing transport and equipment when a soldier appeared at the door and summoned me to a private meeting with Captain Leconte.

11

BESIDE THE STILL WATERS

When I entered his office Leconte was standing at the window looking out to the north. Without a word he beckoned me to join him and I saw in the distance flames casting a lurid glow upon the cloudy night sky.

‘It is a sight, is it not?’ he said. ‘The Foret d’Espigny has been set ablaze by German artillery, but already the fire dies away. The fire we face tomorrow will not be so easily quenched, I think.’

‘I wish there was some way I could help, but tomorrow we must go to Paris.’

He turned to me and raised a quizzical eyebrow. ‘Paris? There will be no defence of Paris. It has been declared an open city.’

‘We’re going as civilians, and not to fight,’ I told him. ‘But our mission may be as important as the outcome of any battle.’

‘Ah yes, your secret purpose. I don’t suppose it matters now if you tell me or not.’

‘All I know is that the future course of the war may depend on it.’

‘Then let us hope the war will continue at least a little longer, until you achieve your goal.’

I glanced at the map of the chateau which was now pinned to the wall beside a painting of some shepherds in Arcadia. ‘Surely it would be better for you to retreat, join the rest of your army and regroup?’

Leconte frowned. ‘To what end? It is no secret our government is resolved on surrender.’

‘Then why make this impossible stand?’

He turned back to the window and gazed out over the benighted land.

‘Many of my men are from this region. I myself was born only a few miles from here. A man can only abandon so much before he sickens of it. We are forbidden to defend Paris, so we shall make our stand here.’

‘But you are so few . . .’

‘We have weapons and we are resolved. The rest lies in the hands of the good God.’

He walked over to his desk and picked up a bottle of Tanqueray. ‘There are many vintage wines stored here, but instead I chose for you this bottle of gin. You English

have a great liking for gin, do you not?’

‘Under the right circumstances, yes.’

‘What circumstances could be better than this? Two soldiers, each on his way to his own battle, like two riders crossing paths in the night. Surely two such men should share a special drink.’

He poured two glasses and handed one to me.

‘When the Germans made their last great assault in nineteen eighteen,’ I told him, slowly swirling the drink around the glass, ‘I had to hold the line with only the depleted remnant of my regiment. The men fought with a tenacity that was scarcely credible, but if the Germans had realised how weak we were they would have destroyed us. We held on in the hope of reinforcement. What is your hope, Captain?’

‘Hope? My hope is that I shall see my wife and children again. My fear is that it will not be so.’

He tapped a finger against his glass, then he said, ‘You have family?’

‘My wife is bent on getting back into uniform,’ I replied. ‘My son is a pilot in the RAF.’

Leconte nodded approvingly. ‘They are fine fliers, those men.’

I felt a chill as I recalled Archie’s prediction of the next phase of the war. ‘They’ll need to be.’

He raised his gin in salute and I returned the gesture.

‘La Garde meurt,’ he toasted, ‘mais ne se rend pas.’

We touched glasses and drank.

We breakfasted at dawn on rations provided by our hosts, this being washed down with a glass of wine for each man requisitioned from the chateau cellars. The Die-Hards had rummaged through the servants’ quarters to scrounge up some civilian clothing and were now decked out in an odd assortment of shirts, collars, ties, waistcoats and jackets. Peter had even found a bowler hat which was perched on his head at a rakish angle. Dougal had arranged our transport and we were collecting our gear when Captain Leconte appeared in the doorway of our quarters.

Approaching Thomas, he spoke to him in a confidential tone. ‘You are a priest, no? If so, it would be a great favour if you would say a short mass for my men.’

‘I am a clergyman, true enough,’ said Thomas, ‘though not of your persuasion. I can’t do you a mass, but I would be happy to lead your men in a prayer.’

‘That will suffice,’ said Leconte with a brisk nod.

All those who could be spared from keeping watch and the preparation of additional defences were gathered in the huge entrance hall. The Reverend Thomas Yowney addressed them from the marble steps while the rest of us kept to one side.

Since meeting Thomas, I had hardly heard him utter more than a few words. Now, however, when the need for it was so great, he seemed to open up a wellspring of eloquence inside himself. As the Scottish chaplain spoke, the lieutenant repeated his words in French. The repetition of each sentence took on the rhythm of a call and response, passing back and forth like a litany.

‘My friends, a time like this brings a man face to face with his religion, and some of you will ask yourselves, Why must such things be? Why cannot God simply make the world a perfect place of peace?

‘God did make the world a place of peace, but He gave us the power to destroy that peace. If we could not do wrong, we would simply be His puppets and there would be no virtue in doing right. In a world without pain or hardship there would be no courage or compassion. If we had no troubles to face, what need would there be for us to even love one another? And so we choose the good, even when that is the hard choice, even when it costs us dearly.

‘And when we have passed through this vale of trouble, will the world be a better and fairer place for all our sufferings? I cannot promise that, for as high as a man climbs, the path is slippery and his weakness drags him down. But I do know this: we all have justice in our hearts. And justice demands that there must be an afterlife, where the hurts of this world are healed and made good, where we will rejoin the dear ones we have lost and sit down to break bread with God Himself.’

As Leconte translated the last sentence, Thomas bowed his head in prayer. At the sight of this, the French soldiers removed their caps and did likewise.

‘The Lord is my shepherd,’ Thomas began, ‘I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; He leadeth me beside the still waters.’

Even without prompting from their commander, the soldiers recognised the ancient psalm and joined in in their own tongue.

‘Il restaure mon âme, Il me conduit dans les sentiers de la justice, à cause de son nom.’

Familiar with the words from our own childhoods, the Die-Hards and I joined in. All of the voices, English and French, filling the great hall took on a sombre resonance, like the harmony of a choir.

‘Yes, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; for Thou art with me, Thy rod and Thy staff they comfort me.’

‘Tu dresses devant moi une table, en face de mes adversaires; Tu oins d’huile ma tête, et ma coupe déborde.’

From the far distance came the first boom of artillery, but the centuries-old song of David rolled on without a pause.

‘Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.’

A final ‘Amen’ arose from everyone at once and the concluding silence hung upon the air like a blessing. Another crash of artillery sounded from beyond the walls and Leconte gave the order for battle. The soldiers crossed themselves, replaced their caps and began to disperse to their assigned positions.

‘I’ve never been much for churches,’ Dougal told Thomas, ‘but you lend a manly vigour to your Bible talk that makes it as bracing as a shot of the best malt.’

‘Your words were well chosen,’ I complimented the chaplain, ‘and so was your prayer. I feel quite bad about leaving.’

‘And from the sound of those guns outside,’ said Jaikie, ‘we don’t have much time to get clear.’

Briskly we followed Dougal out to a garage that lay adjacent to the west wing of the chateau. He presented us with our transport, a blue limousine.

‘It’s a Delage D8,’ he said, jumping onto the running board. ‘We’re travelling in style today, boys. She’s fuelled up and ready to go.’

We stowed our gear in the back and Dougal got behind the wheel.

‘Could you not find a chauffeur’s uniform?’ Peter quipped.

The driver grinned. ‘Another crack like that, Peter, and you’ll be walking to Paris.’

I joined him up front while the other Die-Hards climbed into the rear seats.

The engine spluttered once or twice then purred smoothly as we rolled out onto the driveway. The guards at the gate saluted as we passed by.

‘That’s a fine bunch of lads back there,’ said Dougal. ‘I’d half a mind to stick with them, but we’ve our own fish to fry.’

‘I’m sure there’s a fight ahead of us, if that’s what you want,’ said Jaikie.

‘I never thought I’d be caught up in another war in France,’ I said. ‘I expect many brave men will die before it’s over.’

‘This time we need to be sure there’s a better world at the end of it,’ said Dougal vehemently. ‘There’s plenty of us won’t stand by and let the politicians and the businessmen help themselves to the peace.’

‘You might go in for politics yourself then,’ Thomas suggested quietly, ‘if you’re wanting to remake the world.’

‘Ach, I’ve toyed with the notion,’ said Dougal, ‘but I’d be no good at it. There’s no man alive I won’t offend at some point with the fire and vinegar of my views. Talking sweet and oily to win votes would sit ill with me. No, put me at the head of a mob and I’ll storm the doors of Parliament, or point me towards the barricade and I’ll be the first man to leap on to it. But don’t ask me to go from stump to stump telling each man whatever it is he wants to hear. I’d be calling them rogues and wasters and expect them to cheer me for it.’

‘Well, if ever the times called for a man of action instead of talk,’ said Jaikie, ‘this is i

t.’

‘You know,’ said Peter, ‘you do see some queer sights in wartime. I mind that time we were beating a hasty retreat towards Le Transloy, marching by night to avoid the bombers. There were fires still burning from the day’s shelling, and that helped to light the way. At one point our leading section stopped dead and I went to find out what was up. Everybody was listening to a squeaking noise that was coming towards us. After a few moments out of the smoke and darkness came a soldier in a Balmoral, swinging a tin bucket at his side. It was that that was making the noise.

“‘Man, where in hell do you think you’re going?” I asked him. Says he, showing me his rusty pail, “Ah’m looking for a coo tae mulk.” “Well, you’d best turn around,” I told him, “because there’s nothing behind us but Germans.” “Fair enough,” says he. “There’s another ferm further back. I’ll try that.’” Around he turns and off he goes, completely unperturbed, like he was taking a stroll down a farm path in Perthshire or Angus!’

There was a short burst of laughter in the car, then we heard the drone of an aircraft passing high overhead. Friend or foe, we could not tell. Behind us, we knew, the armoured might of Germany was advancing in an inexorable tide.

Ahead of us lay Paris - and the secret of the thirty-one kings.

PART TWO

THE CITY OF LIGHT

12

A KNIGHT ERRANT

Even as we entered the outskirts of Paris we perceived the sense of doom hanging over the city. There were few people on the streets. Now and then we glimpsed nervous faces peeking out from behind half closed curtains, as if these lingering citizens were afraid of what they might see passing in the street.

There were very few motor vehicles about and almost no one on foot. Even cyclists were few and far between and none of those had the jaunty air they were accustomed to display as they wove casually through the traffic. Some shops were still open for business, but many had shutters over the window and notices on the door announcing they were closed for the duration of the ‘emergency’.

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine Jason and the Gorgon's Blood

Jason and the Gorgon's Blood Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire

Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire Odysseus in the Serpent Maze

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze The Day the World Went Loki

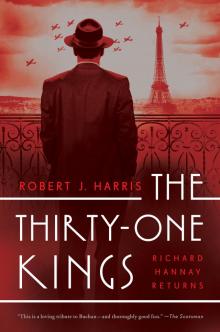

The Day the World Went Loki The Thirty-One Kings

The Thirty-One Kings Thor Is Locked in My Garage!

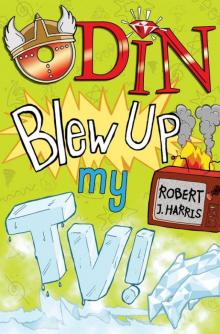

Thor Is Locked in My Garage! Odin Blew Up My TV!

Odin Blew Up My TV!