- Home

- Robert J. Harris

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze Page 3

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze Read online

Page 3

“Yes!” called one of the hunters. “He was a broken reed already.”

“Hardly worth the climb!” shouted another.

“We took this as a gift from the Fates,” Autolycus continued. “But when we field-dressed the beast, preparing to take him down the mountain, we found this embedded in his heart.” He raised his hand and held up something for the company to see. There was a long fragment of bronze glinting between his fingers.

Mentor hit Odysseus on the shoulder with his fist. “Look! Look!”

“My spear point,” Odysseus whispered. “It must have broken off in the boar.”

“This bronze had already taken half the beast’s life,” Autolycus declared, turning towards Odysseus. “The glory of the hunt therefore belongs not just to me and my hunters, but to my grandson, Odysseus, who struck this first deadly blow and took a grievous blow himself in return.”

All eyes turned to the boy on the couch. His name was suddenly on everyone’s lips.

“Odysseus!” they cried. “Young prince of Ithaca!”

Odysseus picked up the walking stick and, trembling, stood. He ran his fingers through his hair, then acknowledged the cheers with a slight bob of his head.

“Tell us the tale, Odysseus,” someone cried.

“How did you do it?” called another.

His grandfather nodded. “The story, my boy,” he said, smiling.

For a moment Odysseus felt nervous. He cleared his throat, lifted his chin. I’ll give them a tale, he thought, that they’ll remember for years. He recalled how the bard had stood, and thrust the stick away. It fell back against the couch. He put his hands on his hips and—never minding the pain in his leg—began the way he’d been taught:

“Apollo’s chariots had scarce cleared the flank

Of Parnassus’ rugged heights—”

“Louder!” someone called.

He made an effort to raise his voice.

“When bold Odysseus’ eagle eye spied out the trail.

Spear in hand, he stalked the fearsome beast.

And then it came—charging through the grass

Like … er … er … a storm that drives over the sea.

With his grandsire’s sturdy spear

Held firmly in his grasp,

He met the fierce attack, unyielding,

Like the rock that er … er … breaks a crashing wave.”

“Go on, young prince,” came a cry, which momentarily broke his concentration, but he took another deep breath and went on.

“The tusks of the boar gouged deep

A dreadful wound on the hunter’s leg.

But as it left him there for dead

It carried its own doom in its heart.”

There was an enormous roar of approval as he finished. But when Odysseus looked over to where Mentor was sitting, his friend had turned his face away.

Odysseus felt a stab of pain in his thigh, as though he’d been wounded a second time. Turning back to the listeners, he raised his hand for silence. “There is a little more,” he said.

The men were silent, waiting, and Odysseus began again.

“But brave Odysseus would not have lived

To tell of his matchless deed

Had not the faithful Mentor,

Friend from boyhood, wise Mentor,

Stood over the injured warrior,

As a shepherd over a smitten ram

From the teeth of a ravenous wolf,

Even at the risk of his own life.”

He did not dare turn again to look at Mentor, but suddenly Mentor’s name was on everyone’s lips. “And there is yet a bit more,” Odysseus called out.

“As unflinching as Parnassus itself,

In the face of the north wind’s fury,

Mentor raised his spear and threw it.”

From behind him he heard Mentor whisper, “Javelin, not spear.” But javelin did not have the force in the verse, so Odysseus ignored truth for story and continued.

“He struck the beast a second wound

And put the widow maker to flight.”

He ended the story by letting his head drop slightly, as the bard had done.

The applause and cheers for his story made him feel good. But even better was the grin on Mentor’s face.

His grandfather, too, was smiling. So daringly, Odysseus called out, “Grandfather, what trophy of this hunt can I take back to Ithaca?”

Autolycus roared with laughter. “Oh, you are my grandson indeed!” he said. “Well …” He pursed his lips. “The tusks will stay here on Parnassus where they were won. They shall be carved into scales for my helmet. But this”—he pressed the broken spearhead into Odysseus’ palm—“will be your trophy. I’ll have my metalsmith drill a hole in it so it can hang by a leather cord around your neck. Let it be a reminder of both your courage and your folly.”

Odysseus smiled. “Grandfather, where there’s victory, there’s no folly.”

Who, thought Mentor, sounds like the old woman now!

CHAPTER 5: DANGEROUS VOYAGE

A MONTH LATER, AUTOLYCUS drove the boys down the coast himself, in a chariot pulled by two large, sturdy horses.

“There!” he cried above the noise of the chariot wheels, the snorting of the horses, and the bellowing of a gusty wind. “The ship to take you home.”

Odysseus looked over to the sandy harbour where the ship was beached. Sailors swarmed over the open deck and tested the mast, the oars.

“Is it big enough, Grandfather?” Odysseus sounded sceptical. “There seem to be only seven oars on each side.” He had arrived in a much larger ship.

“Big enough to carry the two of you and the gifts I am sending home with you,” Autolycus said. He urged the horses ahead with a slap of the reins. “By way of compensation for the injury you suffered under my care.”

Without thinking, Odysseus touched his right leg. The wound was well healed. All that was left was a bright-red scar that Menaera promised would fade after a while, though Odysseus hoped it would not fade altogether.

Mentor laughed. “His father grows rich on Odysseus’ folly.”

Autolycus laughed with him. “Just as well my grandson didn’t lose a leg, or I would have been left a pauper.”

Reining in the horses, Autolycus gave the care of the chariot to a nearby slave. Then turning to the boys, he said, “Come, see all that goes with you.”

By then a cart had come to a halt next to them. The boys watched as three men began the task of unloading the gifts. A pair of bronze tripods, several painted clay bowls, a polished sword, a massive two-handed gold goblet, a casket of jewels, a footstool inlaid with ebony and a fir-wood box carved with pictures of lions and gryphons. They were all taken on to the ship.

“That box looks familiar,” Odysseus said.

“So it should,” said Autolycus with a smirk. “I stole it from your father the last time I visited his palace.”

“Grandfather!” Odysseus said in mock horror. “Stealing from your son-in-law?”

Autolycus grinned. “Just keeping my hand in. He’ll be glad to see it back. If indeed he ever noticed it was gone. And your mother will be pleased with what I am sending her, too: those agate beads she loves so well, and three bronze finger rings. And another ring of white onyx. And Hera only knows what else. Woman stuff. Menaera picked them out for me.” He wrinkled his nose. “And I have something special for Mentor as a parting gift.”

“For me?” Mentor’s voice rose to an alarming squeak.

“For the young hero who saved my grandson. Here.” He handed Mentor a golden signet ring. “Do you see the carving?”

Mentor held the ring up so that the sun glinted on it. “A boar hunt!” he said.

“And finished by my goldsmith just this morning, or I would have given it to you before,” Autolycus said.

“Sir, I’m overwhelmed …” Mentor began.

“Quick, put it on your finger,” Odysseus said, his arm around his friend’s shoulder, “or he�

��ll have it back from you and hidden away before you know it.”

They walked down towards the ship, a black-tarred beauty with a red and white eye painted on its side. Mentor trailed slightly behind, admiring his new ring.

“What was in the box when you took it?” Odysseus asked. “In case Father is angry.”

Autolycus shook his head. “It was empty when I stole it, worse luck. So I’m sending it back just as empty. I may be a thief, but at least I’m an honest one.”

Mentor had caught up by then and heard the last sentence.

They all three laughed at that, Autolycus loudest of all.

At the sound of their laughter, the burly captain of the ship started towards them.

“It’s a fine ship, and a good crew,” he called out. “You’ll be proud, my king.”

Autolycus went to meet him. “Tros, you old pirate.” They grasped hands and began speaking rapidly, one to the other.

“That ship would look better to me,” Odysseus said quietly to Mentor, “if it weren’t taking us back home.”

Mentor refused to be discouraged. He grasped his friend’s shoulder. “But it’ll be a real voyage this time, Odysseus. We’ll be going the whole length of the Great Gulf—not just taking the short crossing to Ithaca.”

Autolycus and the captain had finished their conversation and joined the boys.

“Real voyage, eh?” said the captain, his broad face wreathed by a scraggly beard. There was a slashing scar down from his right eyebrow to his chin. “By sea is quicker. Safer too. You never know what sort of robbers you might run into by the road. Begging your pardon, Autolycus, but you’re—”

“A thief, not a robber.” Autolycus clapped the captain on the back to show he held no hard feelings. “A fine distinction from a seaman who has done some pirating of his own!”

“The sea has its own dangers,” Odysseus mused.

Mentor noted that he sounded more hopeful than scared.

“A few,” Tros agreed, fingering the scar on his cheek. “But we know how to handle them.”

“My soothsayer consulted the oracles not once but twice for this trip,” Autolycus said. “He assures me that you’ll have good weather, calm seas, and a fruitful voyage. And I’ll hold Captain Tros responsible if you don’t.”

“Hold the gods responsible for the seas, not me!” Tros retorted. “I assure you we’ll take proper care of your young princeling.”

“You will indeed—or have me to answer to!” Autolycus warned.

Odysseus made a face.

“Try not to be too disappointed, grandson,” said Autolycus.

Two days later, as Mentor bent over the side of the ship, the last of his breakfast disappearing into the white-capped waves, Odysseus laughed. “So much for Grandfather’s soothsayer.”

Mentor groaned in response. “I’ve nothing left in my belly.”

Black clouds scudded across the sky. Cold winds from the north blown by the god Boreas filled the sail, but the water had turned a dark, forbidding green. Riding high on the waves, the little ship lurched alarmingly.

“Of course,” Odysseus continued, soothsayers only tell people what they want to hear; otherwise who’d pay them?”

Mentor moaned again. He was wrong. There was still some bit of breakfast left, and it too, was threatening a return.

Odysseus patted him on the back. “As I remember, you were the one looking forward to this voyage.”

Mentor’s groan had turned to a constant low moaning.

“Try to enjoy it.”

Odysseus left Mentor to his complaints and found Captain Tros standing with one hand braced against the mast. The sail had long since been hauled down and stowed away, safe from the storm, and the oarsmen strained at their work. The broad-bladed oars knifed into the water in powerful, rhythmic strokes.

“How bad is it really?” Odysseus asked.

Tros looked up into the wind, squinting. “Hard to tell. We could turn back and beach her till the storm passes. On the other hand, we’re only a day’s sail from Ithaca, and we could head there. But that would mean going into the teeth of this wind.”

He saw the alarm in Odysseus’ eyes and misread it. “All will be fine, Prince Odysseus, trust me. She’s a sturdy ship.”

“I’m not afraid,” said Odysseus. He did not add that his alarm was at ending the voyage too soon in Ithaca, where his mother and father would fuss over him and keep him from any more adventures. Till I am an old man, he thought. As old as Tros here.

“All the omens were good when we left,” Tros said. Then he turned and—more to himself than Odysseus—murmured, “Perhaps we can make harbour at Zacynthus.”

For the first time, Odysseus actually smiled and touched a hand to the spearhead amulet around his neck. “The Argo came through worse than this.”

“That it did, Prince Odysseus,” said Tros. Then he turned to shout at the oarsmen. “Put your backs to it, boys! Let me see those muscles rip!”

Odysseus looked for a moment at the straining oarsmen, then he returned to where Mentor was emptying his stomach once again, this time of nothing more than bile.

The storm got worse, not better, with waves breaking over the ship and landing each time with the force of a club on bare skin. Tros ordered the oars drawn in since there was little the oarsmen could do in such a turbulent sea.

All around Odysseus and Mentor, the men began to pray.

“Poseidon, save us,” cried a sailor not much older than Mentor, but well muscled from his time at the oars.

“Triton, hear our prayers,” sang out another.

Either the gods weren’t listening or they weren’t in the mood to grant wishes. Hour after hour, the ship was driven helplessly beneath an olive-black sky. Each new wave lifted her up, then slammed her down again with an impact that made the planks shudder and the men cry out anew.

“Poseidon!”

“Triton!”

“Nereus!”

“Save us!”

Mentor let go of the side of the boat long enough to turn to Odysseus. “This is your fault, you know.”

“My fault?”

A wave splashed between them.

“You forgot to give thanks to Athena.”

“When?” Odysseus asked. “I always remember Athena. I was dedicated to her as an infant.” He started to slip on the wet deck and grabbed on to the railing.

“Well, you forgot this time,” Mentor insisted. “Back at the feast. When you were telling everyone what great heroes we were. You should have thanked Athena for guiding our spears. But you didn’t.”

“It must have …” The crease between Odysseus’ eyes deepened. “Must have slipped my mind.”

“Did it slip your mind that Poseidon’s her uncle?” Mentor said, his face now grey, now green, now … over the ship’s side. He threw up nothing and sank back on to the deck. “The god of the sea.”

Odysseus sat down next to him and put a hand on Mentor’s shoulder. “If someone forgot to thank me for something, I wouldn’t punish a whole boatload of sailors for it.”

“You’re … not … a … god,” said Mentor and retched again, this time into his own lap. Luckily his stomach was empty.

“Then I’ll thank the goddess now.” Odysseus stood, both hands gripping the railing.

“Owl-eyed Athena,” he called, “forgive this small prince who wanted too much to be a hero.”

Mentor grabbed hold of Odysseus’ tunic and, pulling himself up to stand by his friend’s side, he put one hand on the side of the ship, raising the other to the black sky. “I too, Athena, ask forgiveness that I didn’t remind Odysseus of his duty.”

At that very moment, the ship was pitched up into the air by a great wave, as black as the sky, as high as a mountain.

For a second the little boat hovered between sea and sky, between life and death.

Then it dropped.

Still waving, Mentor was flung overboard into the sea.

Odysseus was quick, but not qu

ick enough. His fingers touched the hem of Mentor’s tunic for a moment before the boy was gone.

“Mentor!” Odysseus cried. He thought he could make out Mentor’s thin figure through a haze of sea spray. “Mentor!” he cried again, his hands gripping so hard on the wooden rail that an imprint was left in his palms.

For a moment he thought about diving after his friend, but he was afraid that he might not be strong enough with his weakened leg.

Just then something smacked him painfully on that very leg. He looked down. It was the fir-wood box his grandfather had given them, come loose of its lashings. He knew it was empty and could see that the lid was sealed with wax to keep the interior dry on the voyage.

Just the thing, he thought.

Seizing the box with both hands, he heaved it over the side of the boat and jumped into the waves after it.

Sure enough, the box bobbed on top of the water. Odysseus kept it in sight and caught up after three hard strokes. Then, holding on to one of its wooden handles, he kicked as hard as he could, his bad leg lagging after the good one, steering the box towards the place where he’d last seen Mentor floundering in the sea.

“Mentor!” he cried, then was sorry he had spoken as a wave dashed into his mouth. It felt like the entire ocean went in, and only a bit got coughed back out.

But Mentor heard the coughing, spotted him, and managed to swim close enough so that Odysseus could manoeuvre the box between them, a handle on each side.

“Hold on,” he called. “We can kick ourselves back to the ship.”

“Gone,” Mentor managed in a voice made hoarse by the saltwater. “Gone.”

Odysseus turned and gulped. An immense billow was rising up behind him like a huge, green, cyclopean wall. When the sea had flattened out again, he saw that Mentor was right.

The ship was gone.

They were alone in the middle of the heaving sea.

CHAPTER 6: MISERY AT SEA

THEY CLUNG DESPERATELY TO the box, saying little, conserving strength. The storm continued to rain down on them, drops as large as grapes, but could add little more to their misery. They were already as cold and as wet as they were going to get.

At last—mercifully—the storm subsided. But still the boys bobbed helplessly, now under a brilliant canopy of stars.

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine Jason and the Gorgon's Blood

Jason and the Gorgon's Blood Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire

Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire Odysseus in the Serpent Maze

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze The Day the World Went Loki

The Day the World Went Loki The Thirty-One Kings

The Thirty-One Kings Thor Is Locked in My Garage!

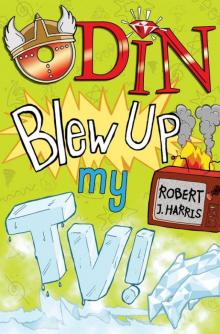

Thor Is Locked in My Garage! Odin Blew Up My TV!

Odin Blew Up My TV!