- Home

- Robert J. Harris

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze Page 4

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze Read online

Page 4

“Where are we?” Mentor croaked.

Odysseus looked up. Suddenly he couldn’t remember any of the stars over them. He and Mentor might as well have been under an alien sky for all that he could name them.

“If only I’d listened more closely to my tutor …” he began.

“If only is not a phrase for heroes,” Mentor retorted hoarsely.

When the rosy dawn appeared at last, all it revealed was an empty, watery plain.

The little box bobbed more gently now on the calm sea.

“Still alive then?” Odysseus called to Mentor. His own voice was hoarse, his thirst enormous. His hands were cramped with hanging on to the handle of the chest.

“Still … alive,” Mentor answered. “I … think.”

“Don’t think,” Odysseus said. “It’s a bad habit. Thinking leads to wondering. Wondering leads to needing. Needing leads to …”

“Then … pray,” Mentor croaked.

Odysseus raised his head. “Athena!” he cried through parched lips.

The goddess didn’t seem ready to answer any more prayers.

And really, Odysseus thought suddenly, since her answers are worse than her silences, perhaps I shouldn’t ask for more. But they definitely needed fresh water. And soon. Mentor was in worse shape than he, having been so ill on board ship. I shall have to keep a careful eye on him.

Suddenly Mentor’s grip seemed to slacken, and slowly, soundlessly, he slid under the water.

Odysseus grabbed for him, caught a bit of his tunic, hauled him up again. Boosting his friend up on to the chest, Odysseus held him in place.

“Better the burning sun than a watery tomb,” he whispered.

Mentor coughed, moaned, lay still.

To keep both their spirits up, Odysseus began to tell stories about his father and the trip on the Argo—about the bronze giant Talos, about the Golden Fleece guarded by the dragon. He wasn’t sure that Mentor was even listening, but he kept on till he had no more voice.

Again and again, he scanned the horizon for some sign—of land or a ship—

A ship!

He blinked three times and looked again to be sure that what he thought he had seen was true.

It was not a cloud, no.

Not the white crest of a wave.

Definitely a ship’s sail.

“Mentor, look!” he cried. “We’re saved!”

Atop the floating chest, Mentor stirred sluggishly and with great effort lifted his head. His eyelids fluttered open.

“A ship!” Odysseus repeated, and let out a huge, hoarse laugh.

There was no mistaking the square shape of the sail now, and—soon enough—a black hull was clearly visible as well.

“What kind of ship?” Mentor croaked.

“The kind that floats,” Odysseus said. “The kind we need. Come on. Let’s get closer.”

He kicked and kicked, the exercise bringing the warmth back to his cold legs, driving them relentlessly towards the oncoming ship.

“Praise to the gods,” Mentor said, his words emerging in an alarming wheeze.

“It was praying to the gods that got us into this fix,” muttered Odysseus. “Let’s just help ourselves, Mentor.” He kicked some more.

Mentor half raised himself up and waved an arm at the ship.

“Over here,” he called out.

“You sound like a frog,” Odysseus said.

“You look like a frog,” Mentor countered.

But they both smiled broadly through cracked lips, and Odysseus kept on kicking.

The ship grew closer still, and they could see figures on the deck pointing at them.

Soon enough they were looking at a row of bearded, bronzed faces, and then a rope snaked down the hull past the painted fish on the side, to dangle in the water in front of them.

“You grab the rope, Mentor, and go up first,” Odysseus said. “Can you manage?”

Without answering, Mentor snagged the rope and started to shinny up hand over hand.

The rope was given a good shake from above, and Mentor slid back all the way into the water.

“No, you idiots,” came a rough voice from above. “Tie the rope to the box first.”

Odysseus bristled at the insult, but they were in no position to argue. So he tied the rope to one of the handles with a firm seaman’s knot.

Almost at once the bearded men began hauling it up.

His remaining strength giving way, Mentor slipped under the water.

Without stopping to think, Odysseus caught him under the arms with one hand, and with the other grabbed hold of the box’s lower handle. Then he held on to both with all his might.

If the sailors above were aware of the extra weight, they ignored it in their eagerness to get their hands on their prize. Soon box and boys were lifted up and over the side of the ship.

Odysseus and Mentor fell to the deck and lay there gasping.

Saved.

CHAPTER 7: A PRINCESS OF SPARTA

“HOI! UP, YOU LAGGARDS!” a voice called above them. Hands dragged them roughly to their feet and shoved them towards the stern of the boat.

Mentor had not the strength to stay upright, and Odysseus had to support him so that he wouldn’t fall forward and smash his face on the deck.

“You look bad enough without flattening your nose,” he whispered.

Mentor didn’t reply.

At the very rear of the ship two girls were sheltering under a sailcloth awning. The boys were shoved down beside them; then their escort rejoined the rest of the crew in examining the box.

One of the girls, heart-faced, with long, delicate lashes and a cascade of curls, shrank back from them. The other, plainer—as the moon is plainer than the sun—smiled a greeting.

“Helen,” she said to her companion, “they are prisoners just as we are. We have nothing to fear from them.”

“Fear’s not the problem,” Helen said, wrinkling her perfect nose and smoothing the folds of her robe. “We don’t know where they’ve come from.”

“From the sea actually,” Odysseus said, propping Mentor against a large water jar. He took a long drink from the jar and then gave some water to Mentor. “Like a god!” He laughed. “But we don’t know where you’re from either.”

Helen turned her head away, as if she disdained both his speech and his manner. The other girl answered for them both.

“I’m Penelope, daughter of Icarius. This is my cousin Helen.”

“Princess of Sparta,” Helen added tartly, turning back to deliver the line.

The conversation had brought Mentor out of his stupor. He smiled weakly at Helen. “We … are—”

Before he could complete his sentence, Odysseus cut him off with a sharp dig in the ribs. Knowledge is a two-edged weapon, Grandfather Autolycus once said. It can easily be turned upon you. He didn’t want the girls—or this rough-looking crew—to know anything about them until he’d figured out what to do.

“I am Eumeneus,” he said. “And this wet frog is my friend Astocles.”

“Really,” replied Helen, raising a regal eyebrow. “And what family do you come from? Are they important?”

Odysseus thought quickly. He knew that their tunics would give nothing away. On board a ship travellers wore the simple garments of sailors, for the salt and sea could ruin good cloth. Better, he thought, to be considered poorer than richer. At least for the moment. Richer might mean they’d be held for ransom.

“No, not important,” he said. “We’re swineherds from Cephalonia.”

Helen immediately drew back, as if a rat had just scurried between them. But Penelope laughed.

“A swineherd who speaks with a courtier’s tongue, Helen.”

“My swine are the king’s swine, princess. A man with half an ear can learn to how to speak like a man of the court.” He grinned, thinking that a good answer.

“Swineherds. Pah!” Helen held her nose as she spoke.

Penelope shook her head. “Since they’

ve just been plucked from the sea,” she said sensibly, “they must be clean. Cleaner than we are, certainly.”

Turning her back, Helen said sniffily, “A clean swineherd is still only a pig keeper. Hardly fit company for princesses.”

Odysseus said nothing, and Mentor sighed and closed his eyes again.

But Penelope turned on her cousin and shook a finger at her. “They’re better, surely, than these brutes who abducted us.”

“Abducted? How?” Odysseus asked quickly, quietly. He’d been right to keep his rank quiet.

“We were walking along the beach collecting shells,” Penelope explained. “Our men were further down the beach, around a bend, collecting firewood, starting a fire. Doing … things. As were our maids. Helen was bored and begged me to go with her.” She bent towards Odysseus and said in a confiding whisper, “You mustn’t mind her. She’s been terribly spoiled. Sometimes it’s simply easier to go along with her than to fight her.”

“I understand, my lady,” Odysseus whispered back, one finger against the side of his nose to show his agreement. Then he said, more loudly, “So—shells, beach, alone and …”

“And suddenly,” Penelope said, her voice matching his, “these brutes appeared from nowhere. From everywhere. We tried to run, but there were too many of them. I almost got away, but then they caught Helen, and she screamed, and I went back for her. I don’t know what happened to our men and our maids.”

“And just see what they did to me,” Helen said. She lifted one of the folds of her tunic to display a tear. “Father had this imported from Crete especially.”

“So they’re planning to ransom you,” Odysseus said.

The girls looked at one another with anxious eyes.

“Not exactly.” Penelope spoke quietly.

Helen leaned forward. “They’re planning to sell me to a wealthy king that he may have the most splendid bride in all the world.” There was a surprising note of pride in her voice. “They mentioned Theseus, the great king of Athens.”

Penelope made a face and turned away.

“Isn’t he an old man?” Odysseus asked.

“He’s an old king,” said Helen. “Rich and powerful. But I wouldn’t expect a pig boy to understand.”

Before Odysseus could answer, a shadow fell across them.

“Get up, you drowned rats,” a broad-faced pirate said to Odysseus. “Captain wants to talk to you.”

Odysseus helped Mentor to his feet, and they managed to make it across the deck to where the captain was waiting.

The captain reminded Odysseus of a mastiff his father owned. Like the dog, the captain was broad at the shoulder and narrow at the knee, and he carried himself with the same air of watchful aggression. Be careful of this one, Odysseus thought, remembering how his father’s dog once bit him on the ankle because he’d moved too quickly near the sheep.

“The box,” said the captain. “Where did you get it?”

Recalling how quickly Penelope had recognised his fine language, he answered with care. “We be simple swineherds, my lord,” Odysseus said, keeping a grip on Mentor’s arm.

“Swineherds, eh!” the captain roared. “And were your pigs doing the dog paddle with the fish?” He laughed, and his men were quick to laugh with him.

“We was chasing a sow who run off, great lord,” answered Odysseus, being careful not to look right into the captain’s eyes. “My mate and me.”

Mentor managed a nod of his head.

Odysseus figured the captain believed him now, else he’d have been stopped. So he went on expansively. “Fallen she had, on to a ledge. So we climbed down to get her. Me first. And my mate’s foot slipped. I grabbed him by the tunic as he went by. Whoosh!” He demonstrated catching Mentor’s tunic.

The sailors began to snigger.

“And he pulls me over with him.” He windmilled his arms to show how he fell.

The sailors were fully enjoying the tale now.

“And into the water went we,” Odysseus finished.

“What about the damned box?” growled the captain. He had, Odysseus noted, teeth like the mastiff’s too.

“Ah, the box,” Odysseus said. “It appeared from nowhere. A gift of the gods, my lord. Keep it if it please you.” He bobbed his head.

The captain let out a short, sharp bark of a laugh and his men all joined in, like dogs around the leader of the pack.

“It pleases me well,” the captain said. “But what should we do about you two pig boys, eh?”

“Let us off at the next habitable stretch of beach?” Odysseus asked. Then, realising that might be too highflown an answer, he added, “A dingle, a shingle, a wee bit of sand would make this pig boy’s life really grand!” He shuffled his feet in a kind of dance.

Again the captain gave his barking laugh. “Indeed, we already have too many mouths to feed—and not enough room at the oars.”

Odysseus nodded his head, trying to show enough gratitude.

“Toss the pig farmers back in the drink,” the captain said.

Three men grabbed Odysseus and dragged him to the ship’s side. He tried to wrench free, but he hadn’t the strength, having spent a night in the water. Besides, they were grown men. Large grown men. Large grown men with muscles. In a moment, they had him over their heads and were about to toss him overboard.

“Wait!” cried Mentor, coming out of his dazed state. “You’re throwing away a king’s ransom.”

There was a long silence, and Odysseus could see before him only the expanse of sea.

“Bring him here,” the captain ordered. “Bring them both here.”

The world turned end over, and Odysseus found himself with his feet back on the deck again. He’d only an instant to recover before he was face to face with the captain once more.

The pirate captain growled at him, sounding exactly like his father’s mastiff. “And what makes either of you boys worth a king’s ransom?” he said. “You look like pig herders to me.”

“You’re wrong,” Mentor said, his voice desperate. “King Laertes will pay handsomely for the safe return of his son.”

Odysseus knew that pirates were merchants—of a sort. Just like his grandfather. Before you steal something, be certain it’s worth the stealing! A prince would be worth keeping, but there was no profit in feeding and tending his companion. However, if Mentor were thrown back into the sea now, Odysseus knew he’d sink like a stone.

I can’t let that happen.

“You’re right, Prince Odysseus,” he said, turning to Mentor. “And if these men were to harm you, your father would surely not rest till he had his revenge. Not even if he had to set after them aboard the Argo herself.”

“Odysseus—what are you talking about?” Mentor asked woozily. “You know you’re the prince, not I.”

“He’s been so long in the water, his wits are waterlogged,” Odysseus said, tipping the captain a sly wink. “Tell me—would a prince wear a cheap scrap of metal like this around his neck?” He pulled the fragment of bronze spearhead from beneath his tunic.

“Not any prince I know,” said the captain. Then he looked Mentor over with a practised eye and, spotting the gold signet ring, he laughed. “Ah, Prince Odysseus, I shall have you—and the ring off your hand.” He turned to his men. “You, Phynos and Tsountas, get rid of this one with the red hair. He’s too crafty for my liking, and see that scar? He’s crippled as well.”

Mentor cried out. “No …”

Odysseus gave him a mighty shove. “Don’t plead for my worthless life, sir. I willingly return to the bosom of Poseidon, knowing you’re safe.”

He rushed to the side of the ship and threw himself over before his deception could be uncovered, flying for the moment through the air like some ungainly bird.

Then he hit the water with a loud splash.

CHAPTER 8: THE THREAD OF LIFE

IN THE BRIEF TIME he’d been aboard the pirate vessel, Odysseus had spotted the one thing that had given him some hope. There had bee

n a flock of seagulls barely visible in the distance.

Where there are gulls, he thought, there must be land.

If he could only make it to land, anything was possible.

A fresh ship.

A sword.

Men to follow him.

He worried about Mentor on the ship more than he did about himself in the sea. It was only a matter of time before Mentor’s unthinking honesty betrayed him. As soon as the pirates discovered the truth, they’d fling Mentor over the side of the boat along with their slops. But only if they were feeling particularly forgiving.

Odysseus swam slowly towards the spot where he’d seen the gulls.

Better thinking than sinking, he told himself. Gritting his teeth, he began swimming with renewed vigour. Both their lives depended upon him reaching land.

Odysseus was actually a strong swimmer when he didn’t have high waves, a weakened leg, and a sick friend to contend with. He’d grown up on an island, learning to swim before he could run. He knew not to rely on one kind of stroke, but to rotate several—an overhand for a few minutes, then a more restful sidestroke, then the overhand again, and finally turning on his back, letting his legs do most of the work.

The last time on his back, he not only saw gulls but could hear them as well.

He flipped over and, lifting his head, tried to catch a glimpse of a shore.

There was a smudge on the horizon that might be an island.

He forced himself onward, stopping every hundred strokes or so to tread water. But lack of food, lack of fresh water, and, most of all, lack of sleep were telling on him. His limbs were growing weaker. He had a persistent headache from the sun and the salt. Each time his arm ploughed through the water, it took a greater and greater effort to raise it again. His legs protested too, especially the right leg. His chest burned as if an iron spike had been driven through it. But still he swam on, now counting the strokes as he went.

One hundred … two hundred … three hundred …

This time the cries of the gulls, which he had taken for encouragement, sounded mocking, as if they were calling out, “Foolish mortal! Neither fish nor fowl.”

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers' Club Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine Jason and the Gorgon's Blood

Jason and the Gorgon's Blood Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire

Will Shakespeare and the Pirate's Fire Odysseus in the Serpent Maze

Odysseus in the Serpent Maze The Day the World Went Loki

The Day the World Went Loki The Thirty-One Kings

The Thirty-One Kings Thor Is Locked in My Garage!

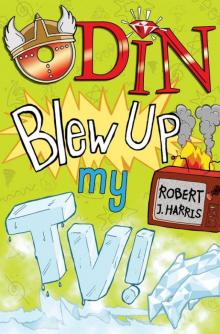

Thor Is Locked in My Garage! Odin Blew Up My TV!

Odin Blew Up My TV!